To anyone coming back from injury: You will climb out of the pit.

There are two kinds of confident athletes: the ones who believe nothing can stop them and the ones who are broken, and come back stronger. This is the story of how I went from the former to the latter.

At the beginning of the 2022 season, I was right where I wanted to be. I won the last tour stop of 2021 in an epic showdown between myself and the reigning women’s world record holder, I trained hard through the off season, and in one of my first record-rated tournaments of the year I tied my PB of 3.5@10.75m.

I’ve never had much fear of speed or velocity — part of what makes me a good water skier — but at this point I was getting brave. I was starting to push the boundaries of the conditions I could ski in, and ski well in. As a newbie to the elite slalom scene, I was trying to make up for a lack of experience in any way I could. I would try anything once.

Coming into May, I was looking towards the US Masters Qualifying Series. The previous year, I attended all 3 qualifiers and did not make the cut. This was my year. In my mind, it wasn’t even a question.

It was a windy day — more windy than most people would ski in. I took a 20mph tailwind 11.25m pass. Gate and 1 ball were perfect. If I can feel this good in this much wind, I can do anything. I had time and space at 2 ball — another win as a left-foot-forward skier. I turned 2 ball and set my sights on 3.

Behind the boat, my alignment shifted — my head went from over my feet to about 8 inches in front of my feet.

I had too much speed and too little fin in the water. My ski released from the water and, in a way, did a Raley towards 1 ball. My ski was over my head. Upside down and at upwards of 65mph, my face was the first thing that hit the water. My head ripped back. That immediate resistance from the water caused the rope in my left had to go tight, instantly tearing the brachialis muscle in my forearm. I continued to yard sale with so much force that my eyelids were forced open the entire time. I saw my ski just inches from my face several times and was certain I was going to take an edge to my face before I lost momentum. I found myself face down in the water, with no physical or directional awareness. I started swimming down, thinking I was going up.

You've just had Whitney's fall. I couldn’t find the surface.

You have to find up.

I felt pure panic for the first time in my life. Somehow, a sliver of logic kicked in. Air is less dense than water; go to the part of your body where you feel no resistance. My feet — I could move my feet freely. I folded at the waist and brought my face to my ankles and finally took my first breath. My parents, who had been training me that day, had both abandoned the boat and swam to me by this point. I tried to take inventory of my body. My left forearm felt like someone had cut through it with a hot steak knife. I remember my mom saying my face was turning black and blue. My lungs were still reeling from the impact. Just floating in water felt like a crushing weight around my ribs and I was struggling to bring in enough air with each inhale.

As the pain from each component increased, I realized that I wasn’t shaking this off.

My parents drug me by my vest to the platform and pulled me into the boat. I kept scanning my body — what didn’t hurt? Was it enough to outweigh the broken pieces? Even in those moments, I was trying to strategize how soon I could get back on the water.

I realized I couldn’t. And for the first time in my life, I felt fear.

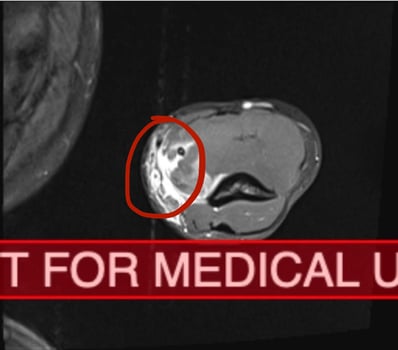

The classic concussion symptoms settled in. I was stunned, confused, dizzy, and my head was killing me. Sound and light hurt. I wanted to go to sleep and never wake up. Within 24 hours, my bicep started swelling. Again my world came crashing down around me as I started to prepare myself for what all symptoms pointed to: a torn bicep. Eight to ten months of rest, and potential loss of some ability. I paid cash for a same-day MRI. As someone who is severely claustrophobic, laying in an MRI machine like salt in the wound.

More fear.

Despite my physical symptoms, my MRI showed that although the swelling and fluid had camped out in my bicep, the muscle itself was intact. I was looking at just that tear in my brachialis. I had a dislocated rib that was pushing on my spine, which explained why I couldn’t get comfortable sitting, standing, or laying down. And they said that if my trap muscles hadn’t been as big as they are, I would have broken my neck.

New fear.

Still, I was in the gym three days later. I spent the next three weeks “doing as much as I could, without pain” — doctor’s orders. And with that, my arm healed and my rib settled back in where it belonged.

But my head? Not so much.

My first time back on the water, I just rode down the lake behind the boat. Can my forearm bear the load? Can I balance? Can I go fast again? Do I even want to go fast ever again? Will I ever have control of anything ever again?

I spent months in a place I can only describe as the bottom of a pit. I watched as everyone at the top have the season I wanted — my season. Never in my life had I wanted to just participate so badly. I didn’t need to win another event ever again; I just wanted to ski. Every week that went by where I was seemingly going nowhere, I watched the people in my life start to pity me. I knew when they said It’s going to be ok, you’re going to get past this! that they didn’t believe it. My hope was the only hope there was, and it was dwindling. I lost countless nights of sleep. I started to notice other markers of long-term concussion symptoms: irritability, anxiety, loss of focus, confusion, fatigue.

There were many days when I went all the way to the lake only to not have the will to try to ski. Every time I turned 2 ball, I saw that fall at 3. I didn’t run 2 consecutive passes for weeks on end — even my opening line length. I started to understand where everyone’s pity came from. I also started to see why people said any success I had had was a “fluke” or “one-hit-wonder.”

Not only is the bottom of the pit dark, it’s lonely. Very few people have ever had the fall I’ve described. So when I say no one understands what it’s like, I’m not exaggerating.

And no one wants to hang out with someone in the pit.

I begged my coach to just let me retire. After 6 months of no improvement, someone needed to call time of death. He told me you can quit but I know you well enough to know that you’ll never forgive yourself. We fought through practices. I cried. I told him how much I hated everything and everyone and that I just wanted to be done and walk away. But I could never get myself to pull the trigger.

Even though I didn’t ski every day, I still showed up to the lake. I knew I needed just one thread of hope to start my climb out of the pit. My coach and my husband always showed up for me, in spite of how painful it must have been for them to watch me suffer. In spite of how awful I probably was to be around. I never knew how much of it was me and how much of it was behavior symptoms that were still out of my control. I retreated inward.

I entered and skied in a couple tour stops with my husband. I was hoping that something about that familiar environment would snap something back into place. It didn’t work. More pity. More You don’t look like yourself!

Caption: Dread and fear on the starting dock at the 2022 Hilltop Pro Am.

Caption: Dread and fear on the starting dock at the 2022 Hilltop Pro Am.

Why are you on your back foot? Because I’d rather go out the back than out the front again.

Maybe it’s time you find another hobby.

People started to look at me the way you look at a dog that you know needs to be put down. You need to think about your quality of life. You seem so unhappy. You can’t force something that isn’t meant to be! Maybe this is a sign?! It felt like the walls were closing in. All signs pointed to my ski career ending before it even started.

Caption: After my physical therapist told me to prepare myself for the fact that my physical literacy might not ever be the same again.

Caption: After my physical therapist told me to prepare myself for the fact that my physical literacy might not ever be the same again.

In November, my coach said that he had a ski he wanted me to try — one that he thought would make me feel safe because it was a little wider underfoot and would be fun to ride. Fun, something I had grown very unfamiliar with. To my surprise, he took the boots off his own ski and handed it to me. A different brand of ski? But, in my mind, what value was I to my existing sponsors anyway? I was at my all-time worst with no end in sight.

What if this was a shot?

I put my boots on the ski and for the first time in months I felt a little like myself on the water. I felt hope. I started skiing more and running more passes. The brand said they would be honored if I rode their ski in the final tour stop of the season — I couldn’t understand why. No brand in their right mind picks up a skier on their decline, but who was I to turn away one final chance? I trained as hard as I could. I could not yet abolish my fear, so I trained alongside it. Fear and I would have to coexist for the time being. In those 2 short weeks, I went from hopeless to running a 11.25m pass in a prelim round on tour.

Caption: In spite of myself, I placed 6th at the final tour stop of the 2022 season, with just 2 weeks of real training under my belt.

Caption: In spite of myself, I placed 6th at the final tour stop of the 2022 season, with just 2 weeks of real training under my belt.

I grabbed up a little higher on that thread of hope and started my climb out of the pit.

It took months of incredibly conscious and consistent work to become comfortable with the same amount of speed, velocity, and torque that I once was. Inadvertently, I developed a new level of patience. Every month was a few more feet that I climbed out of the pit. It wasn’t until April the following year that I started to ski like “old Elizabeth,” as we called it.

Almost one year after my crash, I ran 3@10.75m — a season best — in the first event of the US Masters Qualifying Series to qualify myself for the US Masters. The score was later revised and my qualification was revoked, but it didn’t matter. I got what I actually came for.

I saw the edge of the top of the pit, and I was no longer afraid.

On June 17, at a 4-round record-capability tournament in Hobe Sound, Florida, I ran 3@10.75m again — a score that stuck and moved me back to 8th on the world rankings. Back to where I ranked pre-injury.

I think I can do this.

On June 24 - 25, I ran 3@10.75m in rounds 2 and 3 at the Botaski Pro Am in Seseña, Spain. A set of backup scores that moved me into 7th in the world, a career-highest rank. I finished 4th overall in the event.

I know I can do this.

Caption: Pure joy.

Caption: Pure joy.

This isn’t old me, this is a better me. Anyone with a half trained eye can look at my skiing today and notice that it’s better. This me knows that there is still so much to be learned and experience to be had, and I am ready for it. I am ready to fail, succeed, win, lose, and — most of all — try. Now, my fearlessness comes not from a place of ignorance, but premeditation.

It’s easy to be confident if you’ve always lived your life at the top of the pit. And I hope you never see the bottom of the pit, but if you do, the climb out is worth its weight in gold. You don’t have to find all the answers all at once. You don’t have to change monumentally in a day, a week, or a month. You might have support — you might not. You don’t have to prove anything to anyone. But you can’t stay there forever.

I hope you find your thread and start your climb.

About Parity

Parity was created in 2020 to unapologetically work toward closing the gender pay gap in sports, benefitting both elite women athletes and their fans. Founded by former leaders on Wall Street, the company drives revenue to pro women athletes by using proprietary data analytics to curate sponsorship opportunities, digital collectible sales, and more. With a current roster of more than 800 athletes from 70 sports and 30+ corporate partners, Parity is revolutionizing the financial model for women athletes. To learn more, visit www.paritynow.co

About Group 1001

Group 1001 Insurance Holdings, LLC (“Group 1001”) is a technology-driven financial services company with a mission to empower customers, employees, and communities by making innovative products accessible to everyone. Group 1001 strives to demystify how insurance and annuity products are purchased today by leveraging technology to provide intuitive financial solutions for all Americans. As part of its mission, Group 1001 invests in strategic partnerships to connect with and transform communities through education and sports. As of December 31, 2022, Group 1001 had combined assets under management of $58 billion and comprises the following brands: Delaware Life, Gainbridge, Clear Spring Health, Clear Spring Insurance, and Clear Spring Life.

Follow Parity on Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, and TikTok to stay up-to-date on news surrounding elite women athletes and sports marketing.